Cleveland family members to trace 1924 Olympian’s journey

Updated: Jul. 26, 2024, 5:43 a.m. | Published: Jul. 26, 2024, 5:30 a.m.

Cleveland.com

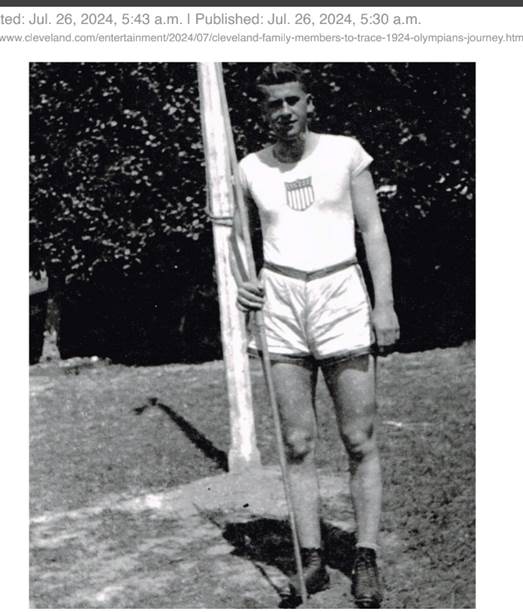

Gene Oberst, a fascinating athlete with multiple interests, won a medal in javelin for the United States in 1924 in France. Several of his descendants will retrace his journey and attend the 2024 Summer Games in Paris. Courtesy of Rob Oberst

By Marc Bona, cleveland.com

CLEVELAND, Ohio – When the javelins slice through the air during the Summer

Olympics in Paris, a few Clevelanders at Stade de France might get a bit emotional as the crowd cheers. They will have a connection, but it’s not with anyone on the field in front of them. It’s a bond that goes back 100 years.

As the world gets ready for tonight’s opening ceremonies from Paris for the Olympics, Gene Oberst will be remembered by his family, including several in Cleveland. Oberst won a bronze medal in Paris in 1924 in javelin.

Oberst’s story takes him from his Kentucky roots to playing college at Notre Dame under legendary coach Knute Rockne to the Paris Games to his life in Cleveland.

“He was kind of a Renaissance guy,” said his son, Rob Oberst of Solon.

He was born with “deformed, club-like feet and could never run fast,” he said. “But he was a pretty good pitcher and planned to be a pitcher at Notre Dame.” In part because of his size – 6 feet, 5 inches, 205 pounds – he also played football.

“He was the slowest man on the line,” Oberst said. But for his junior year he found a way to alter his leg braces, and he gained speed. He blocked for the famed Four Horsemen as well as George Gipp (“Win one for the Gipper!”). He was close with pioneering coaches Rockne and Amos Alonzo Stagg.

One day, while walking on campus, a javelin landed near Gene, annoyed at how close the spear had come.

“So he picked it up and threw it way over” the head of the guy who had thrown it, Rob Oberst said. “The next day Rockne recruited him for the track team.” They didn’t have spare uniforms, so he was given a pair of baseball pants, football spikes and Rockne’s sweatshirt that “came down to his naval,” he said. Amazingly, he threw that weekend, days after picking up the sport, and had a record-setting competition. The roots of an Olympian had taken place.

The top four javelin throwers were selected for Paris, and he finished fifth. But before qualifying he had the furthest throws in competition, so organizers made an exception and included him on the 1924 U.S. team. This was the Olympics featured in the 1981 movie, “Chariots of Fire,” with the religious backstory swirling around English sprinters Eric Liddell and Harold Abrahams.

It would be three years until Charles Lindbergh would fly across the Atlantic Ocean, so everyone traveled by ship to the games. Gene spent about a month and a half overseas. Athletes roomed two per room in 10-room plywood cabins. It was a de facto Olympic Village.

“They didn’t want the athletes to be that close to the city because they feel they’d be tempted by the nightlife and ladies of the evening,” Oberst said. “So they had them stay out in a rural area right on top of Versailles. That was a wonderful experience being out there. They’d take buses and cabs into town all the time to see sights of Paris. They spent a lot of time going back and forth.”

Gene Oberst was used to carrying his own javelin. But when he arrived at the Games he learned that the organizers supplied javelins for the competitors. He was used to shaving his javelin, striving for perfect balance. The inferior javelins were wobbly.

On a rainy, sloppy day, Rob Oberst said, his father threw. He endured a disqualified, out-of-bounds throw. But he salvaged his chances with a subsequent one. He won bronze but, surprisingly, in later years, he didn’t talk much about it.

“I wish I would have asked him more questions,” Oberst said.

Michelle Wagner-Skinner, Rob Oberst’s grand-niece, never got a chance to meet Gene. She was born six days before he died. Last year, though, the family started musing about having some of the younger generations go to Paris, a symbolic show of support for Gene, who died in 1991.

Wagner-Skinner, a physical therapist and seasoned traveler who lives in Cleveland’s Gordon Square neighborhood, didn’t hesitate when her mom forwarded an email last year inquiring about going to the Games.

“Any chance you’d be interested in this?” her mom wrote.

Planning started. She, her husband Peter Skinner and her sister Sarah Wagner will leave Tuesday, Aug. 6, for France, and depart Friday, Aug. 9, for other parts of Europe. On Aug. 7, they will be in Versailles, because the U.S. athletes stayed north of there in 1924.

“That was his base camp,” she said. “He explored Versailles a lot.”

In fact, Gene Oberst kept a detailed journal about his trip. During the passage he saw boxers and fencers work out, watched movies on deck, recorded other ships passing, sang with a group and attended Mass. For practice, he and his compatriots fixed a rope to javelins and heaved them overboard, able to retrieve them.

“The villages en route to Paris were so quaint that I thought sometimes I was transported to the

15th Century. Every house that had a yard had vines and flowers growing all around. We passed hundreds of straw thatched homes and on many of these were flowers growing at the apex of the roof. …

(“In Versailles) I felt as if I was in Paradise. The magnificence of it all forced me to say to myself that I would like to live there in its shadows forever. I don’t think man could possibly construct anything more grand than this place. …

“I was very satisfied with the result since we Americans were not expected to place in the javelin throw. I had no idea that I would secure a place. I entered the meet in a care free way intending to throw the best I could.”

Wagner-Skinner said they also plan to attend a bronze-medal field hockey game in Yves-du-Manoir Stadium – the same venue where Gene won his medal. They will visit the World War I cemetery, just a few years old when Gene visited but filled with monuments now, east of Paris.

“It’s only a week and a half away and it doesn’t feel real,” she said. “Watching the opening ceremonies will be ‘Oh, this is about to happen.’ He’s been such a big, legendary figure in my life.”

After the Olympics, Gene Oberst’s love of books, especially history, translated into his career as a professor. He had started coaching high school, then moved to the college ranks. Tom Connolly, who Rob Oberst said was Rockne’s last football captain and who won two national championships at Notre Dame, asked Oberst if he would coach linemen at John Carroll.

He wound up staying at the school as a coach, political science and history teacher and, for a while, athletic director, between 1935 and 1971.

“He loved teaching,” Oberst said. “He was a very popular teacher.”

This photograph is of the official poster Olympic Games in 1924. Associated Press Then, John Carroll had a policy of mandatory retirement at 65, Oberst said. But the student body petitioned, and he stayed on for five more years.

“He loved Cleveland,” he said.

Gene sold real estate on weekends, painted more than 200 pictures, wrote songs and penned stories, and even started writing an historical novel. He did the cooking at home and was an “upbeat dad,” Rob said.

“His paintings were all over my grandparents’ house,” Wagner-Skinner said. “I knew about the medal. He was this really cool figure in my family, an Olympic athlete and an artist, very kind of a Renaissance man. I honestly don’t think the emotions are going to hit until I am there.”

1924 Olympic javelin results Gold: Jonni Myyrä, Finland – 62.96 meters (207 feet). Silver: Gunnar Lindström, Sweden – 60.92 (200). Bronze: Gene Oberst, United States – 58.35 (191).

Note: Gene Oberst was the first American male to win a medal in javelin for the United States. American men won in 1948 (silver), 1952 (gold and silver) and 1972 (bronze).

More info: Rob Oberst has authored two books about his father: “Gene ‘Kentuck’Oberst – Olympian: All-American & Notre Dame Football Champion” (2016) and “Renaissance Olympian: Mentored by Rockne